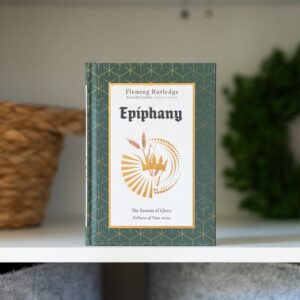

A Review of Fleming Rutledge’s Epiphany

In 2022, InterVarsity Press released Lent by Esau McCaulley, the first volume in a series of short books on the liturgical calendar. Since then, The Fullness of Time series has rounded out with volumes on Pentecost, Advent, Christmas, and most recently, Epiphany. The Fullness of Time authorship is shared by several Anglican priests (Emily McGowin, Esau McCaulley, Tish Harrison Warren), a Pentecostal bishop (Emilio Alvarez), and an octogenarian Episcopal priest, the Reverend Fleming Rutledge. Rutledge has remained, throughout her forty-some-odd years as a priest, a bastion of orthodox, reformational writing and preaching in the Episcopal Church. Moreover, her critically acclaimed works on Advent and the Cross have ushered Anglicans and non-Anglicans alike into a deeper appreciation of the Advent and Lenten seasons. As such, Rutledge’s Epiphany, her contribution to The Fullness of Time was predictably rich, devotional, and deeply christological. That’s just who Fleming Rutledge is.

Rutledge’s presentation of the season of Epiphany is inextricably bound to her understanding of the glory (doxa) of God. Because the word “epiphany” itself means “manifestation” or “unveiling,” the Church has always held the Epiphany season as a time to reflect on the glory of God manifested in the God-man, Jesus Christ (or, as the beloved Anglican hymn attests, “God in man made manifest”). For this reason, Rutledge writes, “To be sure, all of the church calendar is formed around Jesus, but there is a sense in which Epiphany is the most specifically christological season” (10).

Rutledge begins Epiphany with a prolonged reflection on the glory of God. She contrasts the effervescence of human glory (the sort of “glory” Beyonce receives when she wins yet another Grammy) with the indelible, irreducible glory of God. The glory of God most often manifests in Scripture as a divine radiance, the very essence of God that, once manifested, can be deadly. This is why Moses has to be tucked away in the cleft of a rock when the glory of God passes by. A true epiphany, or manifestation of God’s glory, is like a “devouring fire” (Ex. 24:17). Rutledge writes, “We should not come to an epiphany too quickly, before we absorb the message from the burning bush: ‘Stand back! Too hot to handle!’” (26). Nevertheless, to see, experience, attest to, and live in the light of God’s glory is the reason for human existence. Rutledge helpfully points to the first sequence in the Westminster Shorter Catechism as proof: Q. 1, “What is the chief end of man? A. Man’s chief end is to glorify God, and to enjoy him forever” (emphasis mine). Likewise, the chief end of the Epiphany season is to show forth God’s glory as revealed to us in Jesus Christ so that we may glorify and enjoy him as we await his final epiphany in the second coming.

The lion’s share of Epiphany is devoted to unpacking the themes of the Epiphany season through which God’s-glory-through-Jesus is revealed. Rutledge names those themes:

- 1. The visit of the Magi

- 2. The baptism in the Jordan River

- 3. The miracle of the wine at the wedding at Cana

- 4. The transfiguration in the presence of his chosen disciples

Though it is outside the purview of this review to adequately unpack each of these themes, you will find yourselves immersed in them as you worship on Sunday mornings at Christ Church during Epiphanytide. Later lectionaries added to the ancient tria miracula[1] and Transfiguration the stories of Jesus’s commissioning of his disciples, his exorcisms and healings, and his teachings. Rutledge devotes a chapter to each of these Epiphanytide themes, always awakening the reader to the critical theme of God’s-glory-revealed-through-Jesus.

One example of this emphasis comes in chapter 7, “The Ministry.” Rutledge begins by renouncing the vogue preoccupation of mainline churches to typecast Jesus as:

“A healer, a moral teacher, a lover of outcasts, a political revolutionary, a threat to ‘institutional’ religion, a spiritual guide, an example to emulate, and to be sure a numinous personality—but not as the Son of God, the judge who is to come, the Lord of the cosmos, the second person of the blessed Trinity” (98).

The problem, Rutledge states, is that all of these pigeon-holing roles “work under the assumption that Jesus is dead” (98). A dead Jesus can only manifest past glory. It is easy to manifest past glory—ask any former high school or college athlete. They will be able to recount, in high-def surround sound, the heroic moment when they threw the perfect pass or scored the winning touchdown. The trouble with past glory, however, is that it has absolutely no bearing on the present reality. If Jesus is dead, his miracles, teachings, cross and Passion are flashes in a stone-cold pan. If he is alive, they are our salvation. The difference, Rutledge writes, lies in our timidity or boldness in proclaiming his death until he comes. If we are hesitant to laud and magnify him, she writes, “Perhaps we ourselves have not altogether seen his glory” (98).

The problem, Rutledge states, is that all of these pigeon-holing roles “work under the assumption that Jesus is dead” (98). A dead Jesus can only manifest past glory. It is easy to manifest past glory—ask any former high school or college athlete. They will be able to recount, in high-def surround sound, the heroic moment when they threw the perfect pass or scored the winning touchdown. The trouble with past glory, however, is that it has absolutely no bearing on the present reality. If Jesus is dead, his miracles, teachings, cross and Passion are flashes in a stone-cold pan. If he is alive, they are our salvation. The difference, Rutledge writes, lies in our timidity or boldness in proclaiming his death until he comes. If we are hesitant to laud and magnify him, she writes, “Perhaps we ourselves have not altogether seen his glory” (98).

Nevertheless, as she always faithfully does in her writing and her preaching, Rutledge warns us against the assumption that the reality of God’s glory has anything to do with us. This word of warning comes as an encouragement to Christians who are routinely assaulted by headlines about the ever-shrinking Church. Rutledge writes:

“The glory of God is not dependent upon us. He has graciously revealed it to us in Jesus, but we should not imagine that he is diminished if we are small in numbers. His faithfulness to his purposes for his creation will go forward no matter what size individual congregations might be. God is not dependent upon us, but—amazing as it may seem—he rejoices in us” (143).

As we worship him, reveling in the glory he has revealed to us through Jesus, we mysteriously enter the eternal dance of love between the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The Epiphany season orients us to God’s glory not so that we will fear him or hide ourselves in the cleft of a rock (philosophical or otherwise), but so that we may come face-to-face with the Living Son and fall to our knees in worship.

The word “worship” derives from the old English “weorthscipe,” or “worth-ship.” When we worship, we ascribe worth to something. When we worship God, then, what we are doing is making a truthful claim about his worth—we make a truthful claim about his glory. This is why “worship” is often called “doxology,” literally “a word of glory” by which we magnify God based solely on his God-ness. The season of Epiphany, Rutledge writes, “is designed for the purpose of doxology.” As we encounter Jesus in his life, ministry, and teaching, we see a progressive revelation of his glory. Furthermore, when his glory is revealed to us, we are catapulted into Lent, where we see at last “that the cross of Christ is his glory…the season after epiphany is designed to do just this: to build up ‘from glory to glory’ to the narrative of Jesus’ Passion, crucifixion, and resurrection” (148).

With our eyes fixed on Ash Wednesday, just three weeks from the day I write these words, the Epiphany season serves to urge you onward into a deeper awareness and appreciation of God’s-glory-through-Jesus. If you’ll let her, Rev. Rutledge would love to guide you further and deeper into the fullness of time.

Glory to God,

Mtr. Bree

[1] Jesus’s first three signs by which he revealed his glory