My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?

And about the ninth hour Jesus cried out with a loud voice, saying, “Eli, Eli, lema sabachthani?” that is, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?”—Matthew 27:46

The call came at 10:30 that night.

My son David—who you likely know as the child at church with no regard at all for his bodily limits—was sleeping soundly next to me in our living room. David was a hair over three months old, and we had established this nightly routine. He fell asleep while I quietly read or watched television. The phone interrupted the quiet.

On the other end of the line, my brother delivered words that overwhelmed me: “Daddy died.”

I ran to tell Bree, who until that moment had been sleeping peacefully, just like David. In that moment, grief bowled me over. I had never wept like that, never grieved like that.

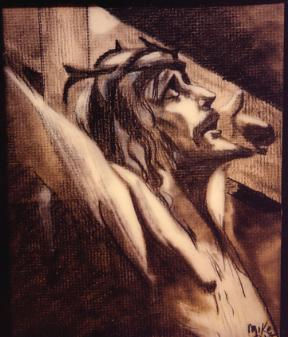

In the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, the evangelists record Jesus screaming out in grief on the cross:

“‘Eloi, Eloi, lema sabachthani?’ which means, ‘My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?’”

Out of the mouth of Jesus, the son of David, came David’s words from Psalm 22.

Out of the mouth of Jesus, the son of David, came David’s words from Psalm 22.

Episcopal priest Fleming Rutledge calls this—“My God, my God, why has thou forsaken me” —the “saying from the Cross … to have if you’re only having one.” It’s only this cry that is recorded in multiple Gospel accounts.

When I was in college and struggling with whether Christianity is true, Jesus’s cry from the Cross brought me comfort. Why, as Tim Keller has noted, would a religion have its hero breathing these words as his last? Why indeed, other than because it must have happened. It must be true.

But as I’ve aged, the meaning of Jesus’s words has morphed from intellectual comfort to necessary empathy. As grief and pain have swept in, I have come to know that His cry is our cry—His cry is the cry to wipe away all tears.

On the Cross, God became Godlessness. Accursed. Convicted. “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin,” Paul writes to the Corinthians (2 Corinthians 5:21). On the Cross, Jesus was shackled “under the dictatorship of sin” for us, Rutledge writes.

Jesus, the God-man, hung on the Cross as the sacrifice for our sins, so that we may not be forsaken. Your suffering, my suffering—they are not in vain, nor is our Savior one who cannot empathize and cannot understand. “For we do not have a high priest who is unable to sympathize with our weaknesses, but one who in every respect has been tempted as we are, yet without sin” (Hebrews 4:15).

Writing about Jesus’s cry of dereliction from the Cross, the writer, minister, and theologian Frederick Buechner says:

“As Christ speaks those words, he too is in the wilderness. He speaks them when all is lost. He speaks them when there is nothing he can hear except for the croak of his own voice and when as far as even he can see there is no God to hear him.”

But, as Buechner notes, he cries out, “My God, my God”: “Not even the cross, not even death, not even life, can destroy his love for God.” And this is the great irony of the crucifixion, isn’t it? Christ’s cry of suffering—His death—means that “whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16).

His agonizing death secured our eternal life and union with Him. What a wondrous love is this.

Charles Snow