The Creeds and the Prayers of the People

After the Word has been proclaimed and preached, the Deacon bids God’s people: “Please stand as we confess our faith in the words of the Nicene Creed.” In this profession of faith, proclaimed weekly in every Holy Eucharist service in the Anglican Communion, Anglicans around the world unite themselves to the 318 orthodox bishops who enumerated this creed at the Council of Nicaea in 325 A.D.

The Anglican Church is a creedal church. The three creeds recognized by the ACNA are the Apostles’ Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Athanasian Creed.[1] For the practicing Anglican, the Apostles’ Creed is recited daily in the Offices/family devotions, the Nicene Creed is recited at every Eucharist, and the Athanasian Creed is recited on special occasions, such as Trinity Sunday. For many Christians, however, this repetitious recitation of the creeds seems novel, even off-putting. Why does the Church need creeds?

Over the last 2,000 years, God has gifted the Church with a beautiful, rich, and thoroughly orthodox tradition. From that tradition arose a series of creeds and definitions, which have defined the orthodox teaching of the Church for centuries. Rather than adding to or subtracting from Holy Scripture, the creeds embody Scriptural teaching and arrange them in coherent statements of faith. Thus, there are three essential reasons for faithful adherence to—and regular recitation of—the creeds.

Over the last 2,000 years, God has gifted the Church with a beautiful, rich, and thoroughly orthodox tradition. From that tradition arose a series of creeds and definitions, which have defined the orthodox teaching of the Church for centuries. Rather than adding to or subtracting from Holy Scripture, the creeds embody Scriptural teaching and arrange them in coherent statements of faith. Thus, there are three essential reasons for faithful adherence to—and regular recitation of—the creeds.

1: The Regula Fidei

First, creeds establish a regula fidei, a rule of faith, which strictly defines the boundaries of what is acceptable Christian doctrine and what is not. Rather than being restrictive, the regula fidei gives Christians the freedom to maintain their distinctive characteristics and identities without stepping outside of the bounds of orthodoxy. Creeds define those boundaries, enumerating the non-negotiable matters of faith and doctrine. The Athanasian Creed begins, “Whosoever will be saved, before all things it is necessary that he hold the Catholic Faith…And the Catholic Faith is this: That we worship one God in Trinity, and Trinity in Unity” (BCP 2019, 769). If a Christian wants to be part of the catholic (universal) faith, he or she must conform to the doctrines enumerated in the creeds. These matters are not extrabiblical; instead, they draw upon the wisdom of Scripture to further define the Church’s teaching on crucial matters.

2: Protection from Heresy

Second, having established a regula fidei, creeds protect the Church from heresy. When individuals or groups step outside of the carefully articulated bounds of orthodoxy, they are no longer part of the Church. The Church has faced heresy since its inception, resulting in the need for clearer teaching on matters of faith. For instance, in the fourth century, a priest named Arius began propagating the notion that “there was a time when the Son was not.” Arius argued that the Son was of similar substance to the Father (homoiousias) rather than being of the same substance as the Father (homoousias). Thus, it has been said that the Church nearly fell apart over one letter! The Council of Nicaea was convened to combat Arius’s dangerous teaching, but more importantly, to solidify the Church’s teaching on Christ’s human and divine natures. As Anglicans recite the Nicene Creed today, we often take for granted that the Church did not always have the luxury of clarity. Thus, if another Arius appeared, claiming that the Son was made, not begotten, we need simply to point to the Nicene Creed to defend the Church from further heresy.

3: Unity in the Church

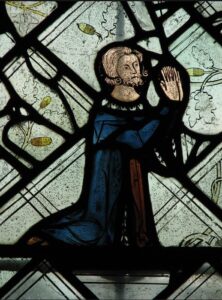

Finally, the creedal tradition unites the present with the past through orthodoxy. When Charles and I do Family Prayer with our 2-year-old son and 6-year-old daughter, we invite them to stand as we recite the Apostles’ Creed. In this recitation, we are grounded in something deeper than our own belief and conviction. We are tethered to the apostles, the martyrs, and the saints of God who have proclaimed the glory and majesty of the Triune God—Father, Son and Holy Spirit—throughout all ages. My children hear the Church’s teaching on what is true and good and beautiful, without the opaque subjectivism of our day. They are steeped in a tradition which was birthed long before them and will continue long after them, as long as the Lord tarries.

Our Creedal Faith

Participation in a creedal faith frees the believer from a desperate attempt to form his or her own regula fidei. It frees him or her from the need to determine whether other Christians with different preferences are inside or outside of the fold. It renders the Church truly “catholic”—universal—across time and space. And it enables the Christian faith to be, as C.S. Lewis described, a hallway with many rooms. The creeds line the hallway. They mark the boundaries of what is “in” and what is “out.” They attempt to keep out robbers and thieves who would sully our belief in the Trinity or the fully divine and fully human Son. But most importantly, the creeds defend and preserve the “faith that was once for all entrusted to the saints” (Jude 3). As we stand and confess our faith in the words of the Apostles’, Nicene, and Athanasian Creeds, we tether ourselves to the great cloud of witnesses assembled at the throne of God, and we worship Him in unity.

The Prayers of the People

Immediately after the Creed, the congregations kneels for the Prayers of the People. Though a designated pray-er offers prayers on behalf of the congregation, the people are not simply listening in as the prayer leader prays. The Prayers of the People are exactly that—the individual and collective prayers of the gathered assembly, offered at once to God.

The 2019 Book of Common Prayer prescribes seven petitions to be included in the Prayers of the People:

The universal Church, the clergy and people.

The mission of the Church.

The nation and all in authority.

The peoples of the world.

The local community.

Those who suffer and those in any need or trouble.

Thankful remembrance of the faithful departed and of all the blessings of our lives.

These petitions cover a lot of ground—they invite us to consider our place in the universal Church, encourage us to think of those who guide and govern us, expand our sensitivity to the sufferings of the world, empower us to pray for co-laborers in our Christian community, enable us to intercede on behalf of the suffering and the rejoicing, and invite us to remember our fellowship with the communion of the saints (for more on the communion of saints, click HERE).

Just as the lectionary frees us from our tendency to return again and again to favored passages of Scripture and the creeds free us from the need to define our own doctrine, the structure of the Prayers of the People frees us to observe a form of prayer that is not dependent upon our own imagination, inclination, or conscience. We pray generally for the nation, for the Church, and for all those in public service, but we also pray for the specific afflictions borne by those who worship at Christ Church. Moreover, when the prayer leader reaches the end of each petition, he or she observes a moment of silence. That moment of silence is for you to respond to God in whatever way you see fit. Some in our congregation vocalize their own petitions. Others simply hold space for the prayer that has just been offered. Still others pray silently, aware of the Holy Spirit’s presence in the moment of stillness. Regardless of your personal preference, the Prayers of the People are an opportunity for every member of the parish to respond to God as we submit all our needs, joys, afflictions, and blessings to his Lordship.

Lord, in your mercy

Hear our prayer.

The Rev. Bree Snow

Deacon | Minister of Formation and Catechesis

[1] Though not a creed, the Chalcedonian Definition is also embraced by the ACNA.